ARTS CONSORTIUM'S ARTIST OF THE YEAR 2021

AMIE T. RANGEL

Excerpt and interview taken from 2021 – 2022 Watermark Publication

Amie T. Rangel has been chosen as the Arts Consortium’s Artist of the Year 2021 for so many reasons. It’s an honor that only comes around once a year, and she is most deserving of the title. Raised in Dinuba, Amie pursued her career in art by first attending College of the Sequoias, then eventually in 2009, she received the Graduate Student Teaching Award and completed her Master of Fine Arts degree from the University of Alberta in Edmonton. Not only is she an artist, she’s also very active in the community – as an advisor for the Chicano Art Heritage Engagement Project (CAHEP), being an active board member of Arts Visalia, involvement with the Museum Alliance of Tulare County, and various curatorial projects. She is currently an Adjunct Professor of Fine Art and Director of the COS Art Gallery at College of the Sequoias here in Visalia. She has received an international award from the Elizabeth Greenshields Foundation and the COS Adjunct Faculty of the Year Award in 2019 and 2021.

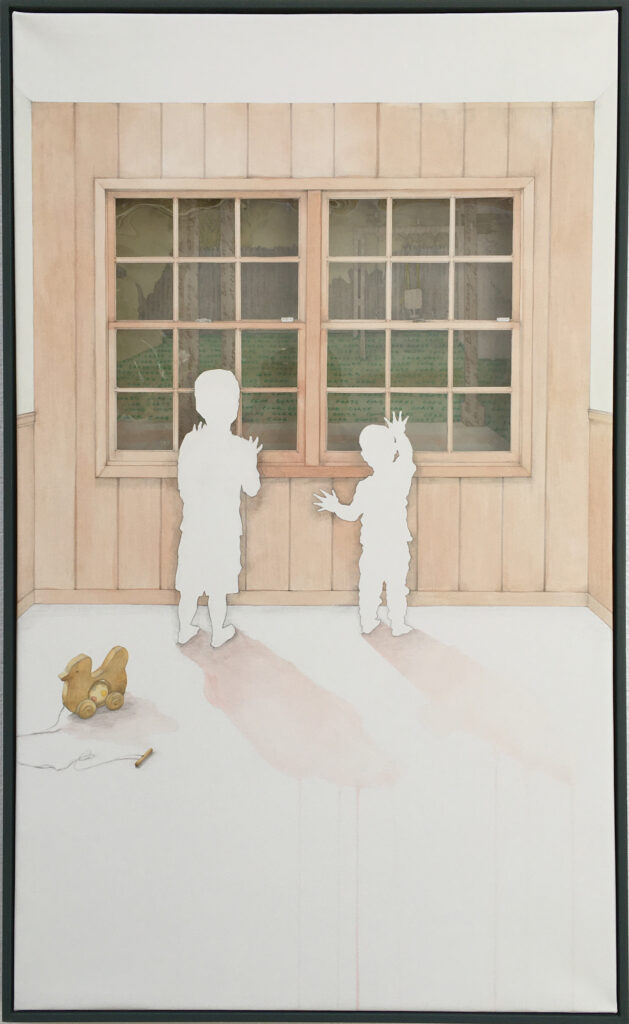

Amie’s view of the world is visualized through her art. Her observations of life and her surroundings are like a journey through time and space – we are fortunate to join her on her visionary voyage through the pieces of artwork she creates with her unique prints, lithographs and drawings. Her life encompasses so much more that her art. An educator, a wife, a mother, a daughter – all these things are reflected on her canvases. Things she observes in her daily life are given meaning, but in an abstract, minimalist way that allows the viewer to decide that meaning for his or her selves. To add their own perspective to the images they see. There are blank spots, incomplete corners, empty rooms, hidden faces, bits of text, unmarked streets and buildings, windows with strange, colorful views that call to the voyeur in all of us – all left to the imagination and our own sense of meaning.

I liken Amie’s work to Hitchcock’s film, Rear Window, where intrigue awaits us if we only look deep enough at the picture and always, there is more than meets the eye. The images allow our own memories and experiences to play on our senses, pulling us into a kind of déjà vu, ending up in a place that is somehow familiar and relatable, even in the abstract. She talked to me about that, being selected Artist of the Year, and more…

What does the title “Arts Consortium’s Artist of the Year” signify to you personally?

I truly feel it validates what the artists in this region are really striving to do – promoting the arts, engaging the community and representing professional, working artists. I’m just one little fragment – one person – in this large community of interesting and engaging artists. It’s really an honor.

You have a strong sense of the environment and community and how these things evolve interjected into your work. Have you always been interested in this idea of change and how it influences and reflects the world around us?

My personal practice is very observation based. My work tends to change and evolve with what’s happening around me. We’ve moved a lot from place to place through the years and I was constantly having to rethink how to adapt emotionally and physically in new spaces and new environments, so I feel like that shaped the way I enter into making work.

Which artists or people have inspired or influenced you?

One of the artists that has taught me so much on multiple levels is Kathe Kollwitz. She was a German artist, drawer, and printmaker – observation based but then did lots of work in the studio. If I could capture the efficiency and quality of her mark making — she is somebody that I continually go back to, looking at her work and feeling like there is always a Kollwitz moment. Another artist is George Tooker – he was working in the 1950’s. I like the fact that he can create these exquisitely beautiful pieces and yet, emotionally as a viewer, they are very unsettling. I don’t know if I would want to be in the spaces that he’s in. I put all that in my visual library and pull it out when I feel I need some of those moments in my own work.

You work in mixed media. What types of materials do you use to create your art?

I primarily make drawings, sometimes prints — whether it be lithographs or a combination of screen prints and lithographs together. I work with colored pencils, graphite, watercolors, paper… my favorite is charcoal, without a doubt. It is the most forgiving and flexible and it can be manipulated in so many ways and you can get such an incredible value range from light to dark. I love it.

How do you find your locations? Do you search for interesting buildings and landscapes that speak to your mindset at the time, or do you just happen upon them? What types of permission, if any, have you had to acquire to work at abandoned building sites?

In one of my previous bodies of work, based off my experience at a dairy facility just outside of Pixley, I approached the dairy farmer and he toured me around his facility. I would go there for three or four hours at first, a couple times a week, and then it was like a couple times a month so I could build from on-location sketches and photographs. If I can, I’ll spend a lot of in-the-field research at that location taking in all the sounds and smells — all of the senses. I feel like I take a lot of notes when I’m on location. When I was in graduate school and I was making the Observation Room series, I took sound recordings and asked the program director if I could go into that space. Let the experience guide where the work is going to go. I just go and start drawing from observation and taking notes. After going to places for a certain period of time, then it’s just taking photographs or taking sound recordings – things that I can bring back into the studio. For some of the Hatchery series which is based off the Badger Creek facility up in Badger, I was able to ask some questions and got permission to go to the site and work there. For the Dwelling series I did in Albuquerque, it was public space – I didn’t go into any of those buildings because people lived there, but I lived nearby and took a lot of walks and would drive by there every other day. That was a completely different type of relationship because I didn’t have to venture far to see it, but there were constant changes, and I would go and walk my dog and see how things had changed. Regarding old, abandoned building, always ask questions. There are ways to find out who owns them — county and city records. When I approached the dairy farmer, I didn’t just drive down a random country road, it was initially through working at COS and asking the Agriculture Department, telling them I’m interested in this project and showing them examples of previous work. It was a long courtship – it didn’t happen overnight. Having visual examples will show what you’re thinking about doing at that location so the person granting you permission will have a better sense of what your intentions are for being there. Through communication and being able to visually demonstrate what your intentions are can help.

Often in your work, it’s the things we don’t see – things you’ve left out of the picture that somehow leave an impression. How do you choose what to leave out? How do you give empty space meaning?

I feel like it’s the editing process and allowing myself to not put in every detail – it’s taken a long time to allow myself that. I want the viewer to be in that space and sometimes if there’s too much detail or too many things, it doesn’t allow that same type of dialogue. I want to give them enough to hold them there, but I also want to give them the opportunity to make it significant to their own experiences and memories or have it connect to a feeling they’ve had before that makes them think of something in their own life.

For our July F1rst Friday, the participating artists included yourself, as well as Laura Melancon, Saegan Moran Brien and Patricia E. Rangel. The exhibition’s title was Lateral Roots: Mothers Nurturing Their Artistic Practice. Can you express what the theme of the show means to you?

Having a group show with other artists I admire and seeing them together – it’s very rare that the four artists that are in the show sit down and have a cup of coffee together, but I’m glad our work gets to do that. They can come together and have a dialogue and conversation. Being able to show with these artists that are also mothers, that are also art educators, I feel it reinforces my own practice – like maybe we’re not as prolific at how many pieces we’re making within the year because our time in the day is consumed by other things, but that we still have that desire to make artwork and continue to pursue this artistic practice. If we didn’t have supportive partners or family members, our parents, our siblings or our friends – having that network, that supportive base, really helps make it possible to pull an all-nighter in the studio, which means that I’m probably not going to be able to make every meal the next day – someone else has to make the coffee!

You say you’re not as prolific, yet the group of you combined is prolific in that you were able to get enough pieces to have an exhibition and maybe that’s what you need to do to have a show at this moment in time.

Yes — when your Executive Director, Ampelio, first asked if I would be interested in having an exhibition, I was worried that I wouldn’t be able to pull off a solo show. I really appreciate that validation — that he felt he could call me and ask and that there could be that possibility. As a curator, I always love the idea of being able to pull different things together, bring them into one space and allow them that opportunity to have a conversation together. After I had a little time to think about what the show could be, I really felt fortunate that he made that call, and it could come together.

As a mother, artist, and teacher, how do you teach or impress upon your own children to appreciate the fine balance between responsibility toward your artistic life and being present as a parent, wife, and teacher?

Ask me this question in 20 years. I don’t know if I have a balance yet, and I feel like I’m okay with that. I grew up with parents that were both very involved in their community and engaged in their professional work. As a kid growing up, seeing how important it was to them and to us as a family, I hope as my kids grow older that through the things Matthew and I are involved in, they will also feel compelled to be engaged in their community.

Has teaching helped you grow as an artist?

Absolutely, without a doubt. I often times will tell my students I get so inspired working and engaging with them. I really feed off how they grow and develop. I try to use my passion for drawing when I’m in the classroom and hope that they will see that even if they don’t want to be an artist, the skills they’re learning can be applied to whatever profession it is they’re planning on going into. All those things that I’m teaching, in turn, inform me as an artist, how to apply some of those things into my own work. It reinforces that I need to practice what I’m preaching.

Windows serve as a distancing device in films – is that also what you are trying to create with the windows in your pieces? A feeling of distance, separation, irony or perhaps a longing for something that lies just the other side of the window frame? In your work titled “Ashes to Ashes: Windows Waiting, Floor 13” there is a window in a room that looks out onto what appears to be chaos and destruction, yet the room itself has a sense of order and calm. There’s so much going on in your work that forces us, as observers, to determine what we actually see, what we think we see, what we don’t see, and the tricks our mind plays on us when we don’t have the whole picture. How did you come up with this particular style to visualize space and time?

I feel like windows – they’re a threshold of some kind, but they don’t service the same type of threshold as a door does.

Yes, doors are like a liminal state between two worlds. You can pass through doors, whereas with windows, you must remain in the one world — you’re stuck on one side.

It has some reference to public versus private, depending on what side of the wall you’re standing on. When I was in graduate school and I was doing research at a swine research facility, they had a series of observation windows that looked into one of the stalls. I created a piece that was the same dimension as those windows and the piece was called Observation Windows. They were two feet by six feet and there was this trigger moment of me thinking about windows, but I don’t think it quite set in at that moment in time. It just planted a seed. Later, when we had moved to Albuquerque, I was making the body of work entitled Dwelling. It was a whole series of pieces. Every time I saw the window coverings in this one apartment complex change, I knew that somebody had moved out and somebody else had moved in. And really, I was fascinated by how often I was documenting that occurrence that was happening in this complex. It was the first time in my work at the time that I wasn’t on the inside looking out – I was on the outside looking in, so I became the voyeur – I became the character looking in on everybody’s windows across the courtyard. I was really captivated by this idea of windows and after I wrapped up that series of work, I started to bring it to the Ashes to Ashes pieces. This was at a time when my dad was at UCSF and I felt like we were in hospital purgatory – you’re sort of in this space, but time is so ambiguous. In that piece, all of the chaos that’s happening outside that particular window – the profile of that is the San Francisco skyline. Most viewers would never make the connection but it’s there because it’s significant to the experience I was having at that time. In my work, I don’t necessarily want to literally tell the viewer every specific detail of what I’ve put in that has significance to me. It doesn’t have to be the waiting room at UCSF, but they’ve had a moment in their life and time where they feel like they’ve been in a space – clean, open, looking out onto chaos – whether it’s literal or psychological chaos.

Tell me about your involvement with the Chicano Art Heritage Engagement Project and what, if any, are your take-aways from working with the project?

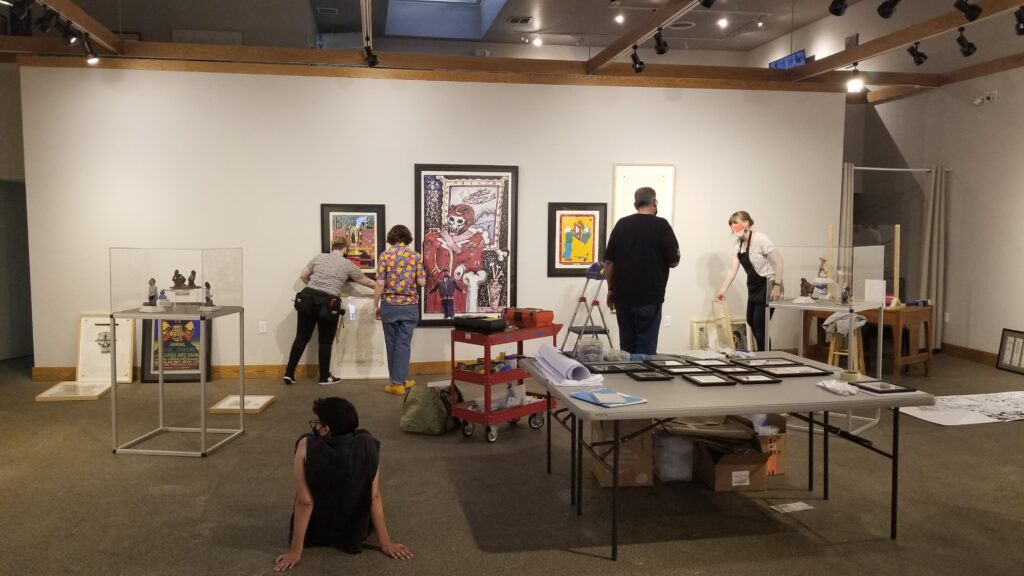

That project really reinforces my sense of “it takes a village” – it takes multiple voices that have multiple strengths and when they all come together, something powerful and really meaningful can be created and a wonderful story can be told. In that project, I feel like I was just one small part amongst this larger group of people that all came to the table at the same time with their expertise and their knowledge. From my end, when the Ricardo Favela exhibition happened at Arts Visalia, I was able to bring some of the visual language and the curatorial aspects to the overall project. I gained so much in thinking about the life of Ricardo Favela. He was truly an incredible and exceptional person. Knowing that he grew up in Dinuba – I grew up in Dinuba – I feel like had I known about him when I was younger, my life would’ve been changed for the better sooner. He was so artistically engaging and someone that really makes you think about honoring your heritage. I’ve tapped into questions like, “Who am I?” and “Where do I come from?” How can I then be more conscious of that when I’m making my own work? In general, being involved with that entire Seen, Unseen project and working with people throughout the community, various faculty on campus, the Favela family, other community partners, and Porterville, was a wonderful opportunity for me to reacclimate myself back to our region. I realized that our region doesn’t exist just within the boundaries of Visalia, but that our Central Valley itself has such an incredible, rich history and this was an opportunity to celebrate it.

What is the art culture like at COS amongst art classes/students? Are there any multidisciplinary art collaborations happening?

Right now, everything is basically via online, but even in the online platform, our Art Department, Fine Arts Division, and probably the campus as a whole has been trying to adapt and create new ways to engage our students with opportunities that can enrich their educational experience. We’re continuing to do visiting artists virtually. There’s still this vital resource for the Valley that we have here at COS and I feel like a lot of the students that go through our program, by the time they leave, have had a least several opportunities to work with faculty on projects together. Like with the Favela project, I was able to have some of my gallery students participate. Some collaborations occur within the campus and not just in the Art Department. Through the gallery, the next show that will be installed will be a collaboration between a national artist and some creative writers through COS that are writing pieces in response to the artist’s work, and they’ll be exhibited together. We, as a department, try to find ways where we can connect our campus to the Art Department. We don’t have an art museum in Tulare County, so I feel like COS needs to serve as a multi-functional place.

Are you currently working on any new projects?

I tend to work on bodies of work – where they’re all thematically working on the same concepts and ideas, and there’s usually a larger title that comes with that – like Ashes to Ashes is a series of pieces and there’s 10 or 12 pieces that are all part of that body of work. This one, the series from the Lateral Roots exhibit, is still in its infancy – I don’t even know what it is yet!

Congratulations on being picked as the Watermark 2021 cover artist! How did the idea for your drawing, Ripping Stories, come about?

It evolved from trying to find different ways of doing things with my kids. Because of the pandemic, we’ve spent a lot of time together. Our younger son tends to rip the pages from the books he really loves, and so I started to save the little bits and pieces of the ones that were beyond repair with the intention of fixing those beloved books. As I was spending more and more time with the boys and also feeling compelled to get out to the studio, this idea came into my mind, so I started to make some compositions. I drew their hands — some from observation and by looking at hundreds of photographs of them and picking out where I could combine different photographs to make the gesture of the fingers in a way that I felt would work well for the composition. People can come to that work and find something identifiable about it that they can make a connection with. Being chosen for the cover is truly an honor. I feel like it validates my personal journey as an artist and mother and as an educator and partner, and where I’m currently at in my life and in my artistic practice – that I’m still here!

Amie is, without question, still here. Through her use of urban landscapes and the shared experience of environmental change and evolution, she is showing us not only how we live, but also revealing to us why we live. Her art speaks on a level that is both personal and universal. What more can we ask of any artist?

Website: https://www.amierangelstudio.com/